Clinical research of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer—current and future concepts

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) represents the third most common malignancy worldwide according to WHO statistics (http://apps.who.int/ghodata/). Not only due to the lack of national screening programs but also because of mostly unspecific symptoms, GC is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage in the West (1). Although radical surgery including D2-lymphadenectomy is considered to provide complete tumor removal, prognosis of GC is still poor. Five-year survival of patients with early GC averages at 75%, but in advanced stages with lymph node involvement it is published to be less than 30% (2). Since the early 1990s, neoadjuvant therapy gained importance for the treatment of locally advanced or initially irresectable GC. Phase II studies demonstrated downsizing effects on primarily unresectable cancer, enabling R0-resections: Further, those studies demonstrated improved survival rates compared to historical trials (3,4). In subsequent years several phase III trials investigated on the role of neoadjuvant or perioperative chemotherapy with different outcomes and results. Some trials focused on the effect of preoperative treatment while others incorporated postoperative chemotherapy as well. To date it is not clear which regimen may be considered standard of care. However, most of the Western countries included neoadjuvant/perioperative chemotherapy as a standard of care in the national guidelines. Although remarkable improvements have been achieved, several issues remain unsolved and are subject to further research.

The present review provides an overview of the most important landmark-studies investigating neoadjuvant and perioperative therapies in GC and tries to sum up the issues that are presently subject of ongoing debate.

Randomized controlled trials

Neoadjuvant or perioperative CT is considered standard of care for the treatment of advanced GC in most European countries and was incorporated into many national treatment guidelines all over Europe, whereas early GC is still treated by primary surgery. This dates back to the results of the British MAGIC and the French FNLCC/FFCD trial, both of which included large numbers of patients and were adequately powered. Both trials directly compared surgery with or without neoadjuvant or perioperative chemotherapy and demonstrated a significant survival benefit for the multimodal approach.

There are a number of theoretical advantages of neoadjuvant therapy over adjuvant therapy for potentially resectable GC (5). The first advantage is the usually better general health condition of patients in the neoadjuvant setting. The clinical experience derived from numerous prospective trials revealed that postoperative chemotherapy is not well tolerated and therefore a significant proportion of patients do not receive adjuvant treatment in clinical practice. Another point in favor of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is that downstaging of the tumor may lead to higher R0 resection rates. Additionally several beneficial effects on occult metastasis or single tumor cell dissemination (micrometastasis) at the earliest timepoint possibly are considered to provide advantages for the respective patients.

The earliest published trial from the Netherlands (6) randomized 59 patients to either receive surgery only or neoadjuvant chemotherapy according to the FAMTX protocol from 1993 to 1996. Preoperative chemotherapy consisted of methotrexat, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), leucovorin and doxorubicin. The trial failed to randomize all patients, which would have been required (225 per treatment group) in order to reach a statistically significant result. Survival was even worse in the intervention arm: 5-year survival rate was 21% for those patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy vs. 34% for those patients undergoing primary resection (P=0.17). The authors concluded that the dismal prognosis of the patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy may be related to the high toxicity of the FAMTX regimen.

Another small trial investigating on the effect of preoperative chemotherapy according to the docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) protocol randomized 55 patients to either receive preoperative chemotherapy or surgery only in Bormann type IV GC. The authors reported higher R0 resection rates without statistically significant differences in overall survival (OS) and postoperative morbidity and mortality (7).

A Japanese trial reported on 171 randomized patients undergoing either neoadjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouridine or primary resection. There was no statistically significant difference in 5-year survival (63% vs. 65% respectively, P=0.698). All patients received oral fluorouridine postoperatively for 2 years (8).

Up to date the MAGIC trial is the most recognized landmark study for perioperative chemotherapy (9). Forty-five centers in the UK, Europe and Asia recruited patients with resectable GC and adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) from 1994 to 2002. Patients were randomized to surgery accompanied by perioperative chemotherapy according to the ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU) protocol (n=250) or surgery only (n=253). Chemotherapy consisted of three preoperative and three postoperative cycles of i.v. epirubicin, cisplatin and continuous 5-FU. There was a remarkably high frequency of postoperative morbidity and mortality unlike in Asian countries, but this effect was not statistically significant. Postoperative morbidity and 30-day-mortality in both treatment arms were reported to be 46% vs. 45% and 5.6% vs. 5.9% respectively. A considerable downstaging effect regarding the ypT- and N-categories was observed for those patients receiving the perioperative intervention. Patients receiving perioperative chemotherapy exhibited significantly improved OS as well as progression free survival (PFS) compared to patients treated by surgery only (P=0.009 and P<0.001). The 5-year survival rate was 36% for patients undergoing the investigative intervention and 23% for patients treated by surgery only (9).

It was widely criticized that many patients in the MAGIC trial did not receive the full number of postoperative chemotherapy cycles because of poor performance status or complications or compliance issues in the postoperative period. In fact only about half (49.5%) of the patients who underwent preoperative treatment in the trial also received the full courses of the planned postoperative CT. Other criticisms included the staging procedures omitting staging laparoscopy, endosonographic ultrasound and PET scans from the study protocol. Therefore it is difficult to claim downstaging of T- and N-status. Surgical quality was not properly assessed which led to poor lymph node retrieval rates and high R2 resection rates.

Due to the uncertain value of the adjuvant component of the MAGIC regimen, this issue was addressed by a retrospective analysis from the UK on a series of 66 patients undergoing perioperative chemotherapy according to the MAGIC protocol. The results of this analysis revealed a considerable prognostic benefit in terms of disease free survival (DFS) for those patients receiving neoadjuvant as well as adjuvant treatment compared to patients who did not undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. However, OS was not significantly different between the two groups. Conclusively, administration of the adjuvant part of the regimen presumably only postponed tumor recurrence rather than preventing it (10).

The French FNLCC ACCORD 07 FFCD 9703 trial basically confirmed the positive outcome data of the MAGIC study (11). The chemotherapeutic regimen applied in the ACCORD trial consisted of 2-3 cycles of i.v. 5-FU and cisplatin. Postoperative chemotherapy was recommended in case of response to the preoperative treatment or stable disease with detection of lymph node metastasis. A total of 224 patients were randomized to either receive preoperative chemotherapy or primary resection. The R0 resection rate among the patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy was significantly higher compared to the surgery-only arm (84% vs. 73%; P=0.04). Postoperative morbidity was reported to be 28% for the patients receiving preoperative treatment and 21% for those patients receiving surgery only (P=0.24). Postoperative mortality was 5% for both treatment groups. Both OS and DFS were significantly prolonged after chemotherapy (P=0.02 and P=0.003, respectively). The 5-year survival rates roughly match those reported for the MAGIC-trial with 38% in the chemotherapy and 24% in the surgery-only arm (P=0.02) (11). However the beneficial effects of perioperative chemotherapy held true only for patients with malignancy of the GEJ.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 40954 Phase III trial investigated on the effect of preoperative chemotherapy only (12). Unlike the MAGIC and ACCORD trials, this study excluded all patients with malignancy of the distal esophagus, as Siewert type I lesions at the GEJ are considered to be esophageal malignancies. Unfortunately the trial had to be closed preliminary due to poor accrual after randomizing 144 patients (n=72 per treatment arm), while 360 patients were initially calculated. In contrast to the previously discussed studies this trial solely relied on preoperative chemotherapy with cisplatin, 5-FU and folinic acid (PLF-protocol). Unlike the other trials adherence to surgical quality and higher grade of standardization was enforced. Resection was performed complying to strict surgical quality standards, including D2-lymphadenectomy. Analysis of the so far included patients demonstrated higher R0 resection rates among those patients having been treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to those undergoing primary surgery (81.9% vs. 66.7%; P=0.036). The trial failed to demonstrate a significant OS and DFS benefit (P=0.113 and P=0.065). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased postoperative morbidity and mortality. However, this difference did not reach significance level (27.1% vs. 16.2%; P=0.09 and 4.3% vs. 1.5%, respectively). During the follow-up period only 66 events (deaths) occurred. The median OS was 64.6 vs. 52.5 months; P=0.466. In order to reach a power of 80% 282 deaths would have been necessary. The fact that higher R0 resection rates did not translate into a significantly prolonged patient-survival was attributed to the low patient number and the higher surgical quality (12).

An important Cochrane meta-analysis was performed by Ronellenfitsch et al. displaying an absolute survival-improvement of 9% at 5 years for patients undergoing perioperative chemotherapy (13). This effect could was detectable for a period of 10 years starting at 18 months after surgery. The odds of a R0 resection in patients treated by perioperative chemotherapy were 1.4 times higher than in untreated patients. No influence on postoperative morbidity and mortality as well as duration of hospitalization could be identified. A possible interaction between age and treatment effect was also considered. No survival benefit of perioperative chemotherapy was demonstrated for elderly patients. Remarkably, in the subgroup analyses a higher survival benefit was detectable for patients with GEJ cancer compared to other sites (13). This observation was reproducible in a large retrospective analysis in Germany. The authors revealed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to survival benefits only when patients undergoing treatment for GEJ cancer revealed histopathologic regression according to the Becker criteria (14). Further it was demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not have any benefits for patients with tumors located distal from the GEJ (15).

The results from the prospective trials and the subsequent meta-analysis revealed a high heterogenicitiy of included patients. Especially the fact that GEJ cancers were included in the trials implies difficulties comparing Western to Eastern Asian patients as it is well known that in Eastern Asia GC is preferably located in the lower parts of the stomach. The results from the French FNLCC study even demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not effective in distal GC patients.

Discussion

Approaches towards multimodal GC therapy largely differ between Asia, Europe and the US: in Asian countries surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is standard of care in the treatment of GC, while perioperative CT has been adopted in Europe and is momentarily being challenged by neoadjuvant chemoradiation. In the US postoperative chemoradiation and just recently also perioperative CT is considered a standard treatment for patients with locally advanced GC. Multiple factors led to the development of these to a large part discordant treatment approaches (16). A recent review article by Merrett concluded that multimodality treatment is considered a standard of care for patients with advanced GC. However, the procedure of choice still remains an issue of debate due to regional differences all over the world.

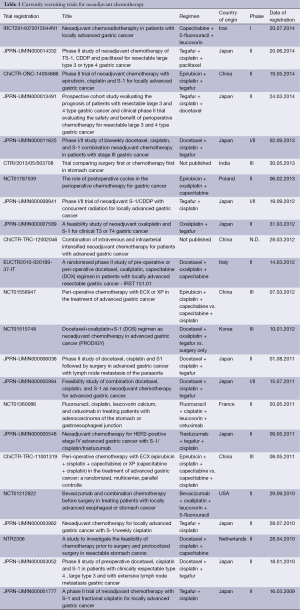

One of the most important surgical quality criteria in the curative treatment of locally advanced GC is an adequate D2-lymphadenectomy. The adherence to this concept varies in different parts of the world. D2 resection has been initially developed by Japanese surgeons, who presently consider any dissection less than D2 inappropriate in advanced GC (17). Just the same adjuvant treatment concepts were introduced in Eastern Asia, which demonstrated improved oncologic outcomes. The beneficial effects adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and stage III GC were proven in a Korean and Japanese trial (18,19). A patient-based meta-analysis, including 3,838 patients from 17 different trials undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy, showed a slight but statistically significant benefit for surgical treatment followed by adjuvant 5-FU–based chemotherapy vs. surgery alone (20). Adjuvant chemotherapy reduced the risk of death by 18%. Furthermore the overall 5-year survival rate was increased by 6%. However, so far there is only rare evident data providing evidence on the application of perioperative chemotherapy in Eastern Asian GC patients. Nonetheless there are several recruiting trials available for patients with locally advanced, marginally resectable GC with poor prognosis, like tumors with paraaortal and/or bulky N2 and N3 nodal disease (JCOG 0001, JCOG 0405), large type III (≥8 cm) or IV (linitis plastic) tumors (JOCG 0210, JCOG 0501, JCOG 1002) and T2-3 N+ or T4 tumors (PRODIGY trial). Currently recruiting trials are listed in Table 1.

Full table

The primary aim of preoperative chemotherapy in Europe was the downstaging of initially unresectable tumors. Promising results led to the introduction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced situations. Since the landmark trial by Cunningham et al., perioperative chemotherapy advanced to the standard of care in Europe. Many opinion leaders from all over the world criticized this trial because of rather poor surgical quality with inadequate lymphadenectomy. Additionally many participating centers had a small case load which led to a high morbidity and mortality rate (9,13). The final result of the underpowered EORTC 40954–trial (12) revealed no significant differences in survival when D2 dissection was performed. This supports the hypothesis that the main effects of perioperative chemotherapy is represented by the fact that it catches up on an inadequate lymph node dissection. This hypothesis is also supported by the results from the INT-0116 trial, in which lymph node dissection was even less aggressive before the administration of adjuvant radiation therapy (21).

Another difference between the East and the West is the disparate incidence of adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus and the gastric cardia (AEG I-III) that is increasing in most Western populations (22-24). In Asian countries junctional adenocarcinomas are still rare (25,26). A meta-analysis and a retrospective analysis of a large single-center cohort provided evidence that predominantly patients diagnosed with GEJ cancer are those who benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy (15,27).

Remarkably, independent of the treatment sequence and modality, a multimodal approach consistently results in a survival benefit when applied in resectable advanced GC. The downside of the mentioned studies is their limited generalizability. While positive effects of adjuvant chemotherapy were demonstrated in Asian populations only, the positive effects of perioperative chemotherapy were proven in a European population of GC patients with a high percentage of tumors located at the GEJ and a less radical lymphadenectomy (9). Additional application of radiation therapy may possibly outperform neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone in GEJ cancer, as it was demonstrated in randomized trials before (28,29). One issue that also needs to be resolved is whether the pre- or postoperative part of the perioperative chemotherapy is responsible for the beneficial survival effects. Since only 54.8% of patients assigned to perioperative chemotherapy in the MAGIC-trial actually received postoperative chemotherapy due to various reasons this issue still remains unclear (9). The Polish STOPEROCHEM trial (NCT01787539) currently focuses on this question. However, first results will not be available before 2022.

Although remarkable improvements for GC patients in Europe and the US were achieved by perioperative/neoadjuvant chemotherapy, only a small portion of patients actually benefits from neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore addition of preoperative radiotherapy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy was advocated to be beneficial. The German POET trial (28) provided evidence that neoadjuvant or perioperative chemoradiation may be an alternative to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in GEJ cancer. Patients with locally advanced GEJ cancer either received two courses of PLF (cisplatin, leucovorin, 5-FU) followed by 3 weeks of combined chemoradiation (30 Gy, 2 Gy per fraction, 5 fractions per week, cisplatin/etoposide) followed by surgery or to 2.5 courses of PLF followed by surgery. The trial had to be closed early due to low accrual. The survival benefit for chemoradiation with a median survival of 33.1 months for the radiation group and 21.1 months for the chemotherapy arm was statistically insignificant. Mortality was higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (10.2% vs. 3.8%), which was not statistically significant (P=0.26). Another study from the Netherlands (CROSS-trial) investigated on the role of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for GEJ cancer in a multicenter, randomized, controlled, phase III setting (29). Patients either received chemoradiation (carboplatin, paclitaxel, 41.4 Gy in 23 fractions, 5 days per week) followed by surgery or surgery only. R0 resection rates in the CRT group were significantly higher compared to the surgery only group (92% vs. 69%, P<0.001). OS was significantly improved after preoperative chemoradiation compared to surgery only (49.9 vs. 24.0 months; P=0.003; HR 0.675; 95% CI, 0.495-0.871), while postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality (4% in both) were comparable in both arms. The still ongoing TOPGEAR trial addresses the question if neoadjuvant chemoradiation may be superior to perioperative chemotherapy in a phase II/III setting (30). Patients diagnosed with gastric or GEJ cancer are randomized to either receive three cycles of ECF according to the MAGIC protocol or chemoradiation (two cycles of ECF followed by 45 Gy radiation accompanied by 5-FU). After surgery both groups receive three additional cycles of ECF. The first part of the trial is going to recruit 120 patients to demonstrate efficacy and safety of preoperative chemoradiation. The second part (phase III) is planned to recruit a further 632 patients providing a total number of 752 patients.

Future studies should consider the patients individual response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy when deciding upon the administration of an additional adjuvant treatment. Patients benefiting from neoadjuvant treatment have to be carefully evaluated in terms of tumor-location and maybe also Laurén-histotype (15,31). An unresolved issue is the application of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with diffuse type/signet ring cell histology not benefitting from perioperative chemotherapy. Messager et al. investigated this issue in a multicenter comparative study including 3,010 patients from 19 French centers including 1,050 patients (34.9%) with signet cell histology (31) and demonstrated that perioperative chemotherapy was ineffective for those patients. The authors concluded that perioperative chemotherapy did not provide survival benefits for patients with signet ring cell histology. In a German analysis, which included 200 patients with diffuse type histology having undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy, only 14.5% showed a histopathologic response according to the Becker criteria (14). In comparison 27.7% of patients with an intestinal type growth pattern (n=331) demonstrated complete or almost complete histopathologic response in the postoperative workup (15). Due to the uncertain value of preoperative chemotherapy in signet ring cell GC a large phase II/III prospective trial was initiated by a French group randomizing 314 patients to receive either perioperative chemotherapy according to the ECF protocol or primary surgery. However, results are not going to be available before 2018 (32).

The potential benefit of neoadjuvant/perioperative chemotherapy in patients exceeding an age of seventy years remains elusive since most of the randomized trials omitted those patients before randomization. This represents a drawback that needs to be overcome, since patient age is being expected to increase in the near future. This current issue is addressed by a recent German retrospective analysis including 460 patients. Preliminary data revealed comparable outcomes for patients aged 70 years and older undergoing perioperative chemotherapy compared to their younger counterparts in terms of survival. However a slight increase of adverse events and the necessity for dose reduction during the course of treatment was notable in this analysis (unpublished data).

The increasing variability of new compounds and regimens is probably going to further improve outcomes after multimodal treatment. A very promising regimen was published by Homann et al. demonstrating pathological complete remission rates of up to 30% (33). The ongoing phase II/III trial is expected to be terminated by 2015 (33). An ongoing British trial (ST03) presently investigates the safety and efficacy of adding the monoclonal VEGF-antibody Bevacizumab to the ECX-regimen (epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine) in a perioperative setting (34). The findings of the famous ToGA-study which revealed the beneficial effects of trastuzumab for HER2-positive advanced gastric and GEJ cancers in combination with a platinum-based chemotherapy (35) gave rise to studies investigating the HER2-positivity in advanced GC with bulky N2 or N3 nodal disease (JCOG2005-A) with possible implications in a neoadjuvant setting. A Japanese phase II study (COMPASS trial) recently reported on higher complete remission rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with four cycles of S1/cisplatin or paclitaxel/cisplatin regimens (36). Further compounds such as panitumomab, catumaxomab, lapatinib and other biologicals are going to demonstrate their potential benefits in perioperative multimodal treatments in the next future. The promising technology of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and HIPEC in a curative setting may demonstrate promising results as well (37).

Response prediction is advocated as an important field of research, as histopathologic response may be considered as a major predictor for survival prognosis (15). Personalized application of preoperative chemotherapy may improve patient’s outcomes by reducing perioperative morbidity due to possibly ineffective neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Although conventional imaging modalities such as endoscopic ultrasound, CT scanning, endoscopy and MRI demonstrated a correlation between response and survival, none of those proved efficient in predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (38). Therefore PET scanning and reduction of standardized uptake value (SUV) in the tumor was advocated as a reliable method to early assess response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients suffering from GEJ cancer (39). The same method has not proven effective for GC located in the distal parts of the stomach. This may be related to the notion that GEJ cancer possibly conveys different biological properties compared to true GC. It was shown that especially signet ring cell GC is unsuitable for response prediction by PET scanning due to its unfavourable FDG (F-18 desoxy glucose) uptake (40). Response prediction in non GEJ cancers therefore remains to be a challenge and is subject to ongoing research for the future. However, a subsequent study was not able to reliably reproduce those results (41), leading to uncertainties for response prediction. Alternatively FLT-PET has been advocated as possible new tool to predict histopathologic tumor regression (42). Nonetheless long term evaluations are not available to date. Due to the fact that imaging modalities appear to be not reliable, molecular markers were proposed as promising predictors of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. It was shown that the expression of the microRNA let-7i was related to the extent of histopathologic response in patients undergoing preoperative chemotherapy for advanced gastric (43). Another marker which was proposed by Schauer et al. is the expression of the Ephrin B3 receptor, which was significantly related to histopathologic response in distal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (44). This was not evaluated in GC so far. However, the concept of microarray based evaluation of novel biomarkers in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy appears to be an attractive tool to identify possible predictors of histopathologic response. Nonetheless the heterogeneity in genetics, biologic properties of the respective patients and applied regimens of treatment pose a relevant problem in finding a reliable and reproducible set of predictors for success of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Future research is going to elucidate this interesting area.

Although multimodal treatment concepts may improve oncologic outcomes, surgical issues should also be addressed in ongoing trials, especially in the Western world where D2 dissection is still not commonly accepted. Surgical training of trial contributors and quality control studies ahead of study initiation should be enforced in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agboola O. Adjuvant treatment in gastric cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 1994;20:217-40. [PubMed]

- Reim D, Loos M, Vogl F, et al. Prognostic implications of the seventh edition of the international union against cancer classification for patients with gastric cancer: the Western experience of patients treated in a single-center European institution. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:263-71.

- Wilke H, Preusser P, Fink U, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy in locally advanced and nonresectable gastric cancer: a phase II study with etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1318-26. [PubMed]

- D’Ugo D, Rausei S, Biondi A, et al. Preoperative treatment and surgery in gastric cancer: friends or foes? Lancet Oncol 2009;10:191-5. [PubMed]

- Ott K, Lordick F, Blank S, et al. Gastric cancer: surgery in 2011. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011;396:743-58. [PubMed]

- Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, et al. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for operable gastric cancer: long term results of the Dutch randomised FAMTX trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 2004;30:643-9. [PubMed]

- Feng LM, Li G, Sun XC, et al. Treatment out come of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for Bormann’s type IV gastric cancer. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat 2008;15:1022-4.

- Kobayashi T, Kimura T. Long-term outcome of preoperative chemotherapy with 5'-deoxy-5-fluorouridine #5'-DFUR# for gastric cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2000;27:1521-6. [PubMed]

- Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11-20. [PubMed]

- Mirza A, Pritchard S, Welch I. The postoperative component of MAGIC chemotherapy is associated with improved prognosis following surgical resection in gastric and gastrooesophageal junction adenocarcinomas. Int J Surg Oncol 2013;2013:781742.

- Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1715-21. [PubMed]

- Schuhmacher C, Gretschel S, Lordick F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for locally advanced cancer of the stomach and cardia: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized trial 40954. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:5210-8. [PubMed]

- Ronellenfitsch U, Schwarzbach M, Hofheinz R, et al. Perioperative chemo(radio)therapy versus primary surgery for resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, gastroesophageal junction, and lower esophagus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD008107. [PubMed]

- Becker K, Mueller JD, Schulmacher C, et al. Histomorphology and grading of regression in gastric carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 2003;98:1521-30. [PubMed]

- Reim D, Gertler R, Novotny A, et al. Adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction are more likely to respond to preoperative chemotherapy than distal gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2108-18. [PubMed]

- Merrett ND. Multimodality treatment of potentially curative gastric cancer: geographical variations and future prospects. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:12892-9. [PubMed]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011;14:101-12. [PubMed]

- Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:315-21. [PubMed]

- Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1810-20. [PubMed]

- GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration) Group, Paoletti X, Oba K, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;303:1729-37. [PubMed]

- Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med 2001;345:725-30. [PubMed]

- Botterweck AA, Schouten LJ, Volovics A, et al. Trends in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in ten European countries. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:645-54. [PubMed]

- Powell J, McConkey CC. The rising trend in oesophageal adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia. Eur J Cancer Prev 1992;1:265-9. [PubMed]

- Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, et al. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA 1991;265:1287-9. [PubMed]

- Okabayashi T, Gotoda T, Kondo H, et al. Early carcinoma of the gastric cardia in Japan: is it different from that in the West? Cancer 2000;89:2555-9. [PubMed]

- Chung JW, Lee GH, Choi KS, et al. Unchanging trend of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in Korea: experience at a single institution based on Siewert’s classification. Dis Esophagus 2009;22:676-81. [PubMed]

- Ronellenfitsch U, Schwarzbach M, Hofheinz R, et al. Meta-analysis of preoperative chemotherapy (CTX) versus primary surgery for locoregionally advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach, gastroesophageal junction, and lower esophagus (GE adenocarcinoma). J Clin Oncol 2010;28:abstr 4022.

- Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:851-6. [PubMed]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. [PubMed]

- Leong T, Smithers M, Michael M, et al. TOPGEAR: An international randomized phase III trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus preoperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer (AGITG/TROG/EORTC/NCIC CTG). J Clin Oncol 2012;30:abstr TPS4141.

- Messager M, Lefevre JH, Pichot-Delahaye V, et al. The impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival in patients with gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma: a multicenter comparative study. Ann Surg 2011;254:684-93; discussion 693. [PubMed]

- Piessen G, Messager M, Le Malicot K, et al. Phase II/III multicentre randomised controlled trial evaluating a strategy of primary surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy versus peri-operative chemotherapy for resectable gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinomas - PRODIGE 19 - FFCD1103 - ADCI002. BMC Cancer 2013;13:281. [PubMed]

- Homann N, Pauligk C, Luley K, et al. Pathological complete remission in patients with oesophagogastric cancer receiving preoperative 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and docetaxel. Int J Cancer 2012;130:1706-13. [PubMed]

- Smyth EC, Langley RE, Stenning SP, et al. ST03: A randomized trial of perioperative epirubicin, cisplatin plus capecitabine (ECX) with or without bevacizumab (B) in patients (pts) with operable gastric, oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) or lower oesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:abstr TPS4143.

- Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:687-97. [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa T, Tanabe K, Nishikawa K, et al. Induction of a pathological complete response by four courses of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer: early results of the randomized phase II COMPASS trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:213-9. [PubMed]

- Sun J, Song Y, Wang Z, et al. Benefits of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for patients with serosal invasion in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2012;12:526. [PubMed]

- Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Role of imaging in predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1650-6. [PubMed]

- Ott K, Herrmann K, Lordick F, et al. Early metabolic response evaluation by fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography allows in vivo testing of chemosensitivity in gastric cancer: long-term results of a prospective study. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:2012-8. [PubMed]

- Ott K, Herrmann K, Schuster T, et al. Molecular imaging of proliferation and glucose utilization: utility for monitoring response and prognosis after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3316-23. [PubMed]

- Vallböhmer D, Hölscher AH, Schneider PM, et al. [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography for the assessment of histopathologic response and prognosis after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 2010;102:135-40. [PubMed]

- Herrmann K, Ott K, Buck AK, et al. Imaging gastric cancer with PET and the radiotracers 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG: a comparative analysis. J Nucl Med 2007;48:1945-50. [PubMed]

- Liu K, Qian T, Tang L, et al. Decreased expression of microRNA let-7i and its association with chemotherapeutic response in human gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:225. [PubMed]

- Schauer M, Janssen KP, Rimkus C, et al. Microarray-based response prediction in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:330-337. [PubMed]